Manhattan’s Landmark Buildings Today written by Ada Louise Huxtable, notable American architectural critic, this article was originally published in Wall Street Journal in 1999 and in the book called On Architecture-Collected Reflections on a Century of Change. It speaks about the cross section of architecture, preservation, real estate and investment. Excerpts below:

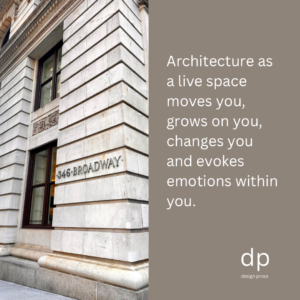

In New York City, Architectural Preservation is real estate driven- but so is everything else. Old buildings must earn their way. And that goes even for the fabled skyscrapers that are legendary stuff of its celebrated skyline. The icons of our modernity, the timeless symbols of the city’s spirit, are showing their age; they, too, are subject to obsolescence and decay and the cycles of real estate boom and bust. The empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the Woolworth Building, the 1930 McGraw-Hill Building and Rockefeller Center either have been radically upgraded or are now receiving a major overhaul.

And while you can’t exactly kick these wonders of the building art around, most suffered vicissitudes of ownership and management over the year, with treatment ranging from Rockefeller Center’s careful stewardship to the outright neglect, ballyhooed Band-Aids, and uninspired remodeling of some of the others. It takes consortiums to buy and sell them, in process involving the financial and legal mechanisms of leveraged investment and complex tax advantages that are the club rules of New York’s property market. Some are kept briefly, like trophies; the Chrysler Building, for example has had numerous owners since its 1930 completion and bumpy existence until its recent purchase by Tishman Speyer after what was reported as fierce bidding war. In today’s explosive economy you don’t pick these things up for a song; the purchase was from another consortium, of Japanese lenders, for something in excess of two hundred millions dollars. The Japanese acquired many of New York’s landmark skyscrapers like status souvenirs during the go-go eighties and have been unloading them ever since. […]

It would be nice to believe that investor interest in these properties has been motivated by their architectural excellence or some sentimental regard. To put it more realistically, art and sentiment are understood and used as marketing tools. They give a competitive edge at a time of high demand. These are the original status or signature buildings. That advantage makes it worth putting money into upgraded preservation. The appeal of the Chrysler Building’s lusciously ornate art deco details of bronze and rare inlaid woods, or the Byzantine splendor of the Woolworth Building’s mosaics, translates into top market dollar. Nor could liberties really be taken, since most of these buildings have been protected as designated landmarks since seventies. But underlying all these calculations is that prime rule and real estate mantra: location, location, location. When choice development site are scarce or require lengthy Machiavellian negotiations, the value of these desirably located landmark skyscrapers soars. […]

Change and continuity, a synthesis of past and present, are the lifeblood of New York. The serendipitous reuse that continually regenerates historic stock is the only kind of preservation that works, but it requires a combination of vision, appreciation, enabling economics and eternal vigilance to keep landmark buildings in the mainstream. Preservation battles are won and lost; there are triumphs and terrible losses, but essentially the system pays off. Old buildings survive because it rarely makes sense in bad times to demolish, while in good times there is every incentive to invest. The city renews and enriches itself when it reuses its landmarks in an economically sound way. In New York, the art of architecture is inseparable from the art of the deal.

Wall Street Journal, May 6, 1999